Preventing counterplay is hard to do

How to tackle the seemingly impossible task of proving your opponent has no good moves

Philosophers have known, since long before chess was invented, that it’s hard to prove a negative. Bertrand Russell pointed out that if he claimed a teapot orbits the sun between Earth and Mars, nobody could prove that he was wrong, because space is vast and teapots are too small to be seen via telescope. To counter his claim, you’d have to somehow examine every location the teapot could possibly be.

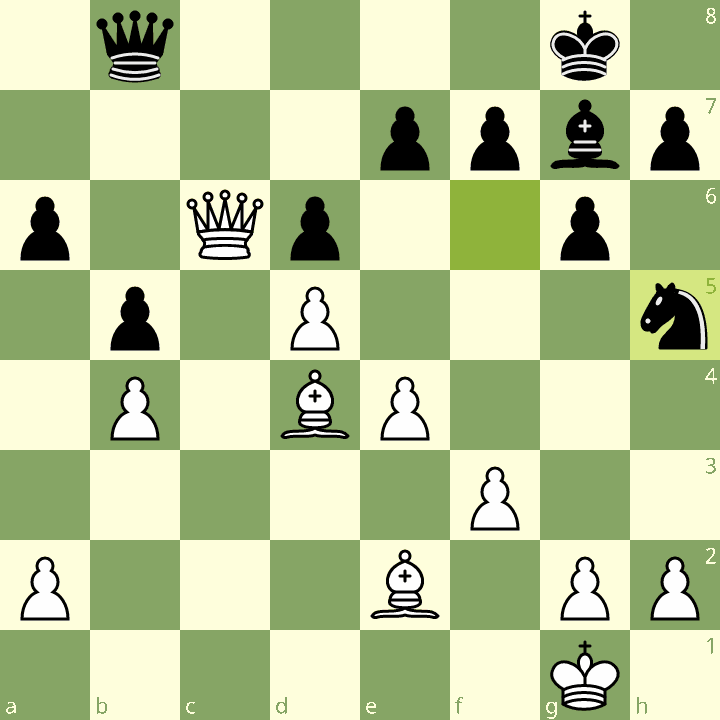

With that in mind, here’s a position I got in a recent game. What would you play?

My first thought was to trade bishops and then play Qxa6, winning one pawn by force, with a second, the one on b5, looking certain to fall as well.

Unfortunately, that would give away white’s entire advantage. It would allow counterplay — the black queen could infiltrate on either the c-file or the newly undefended dark-squared diagonal leading to white’s king, with good chances for a perpetual check.

The best move in the above position is Be3. But figuring that out requires proving a negative.

Does your opponent have any useful moves?

That’s the key question. When you’re coming up with moves and plans for yourself, you just need to come up with one that works. When you’re considering your opponent’s possible moves, you have to consider anything with any potential. And that’s hard.

When you’re preventing counterplay, you have to prove a negative. You’re playing non-forcing moves, giving your opponent a free hand to move any piece they want, and somehow you need to have the belief that they won’t be able to do anything useful.

The task for a chess player when preventing counterplay is simpler than finding Russell’s teapot. Your opponent has a finite number of legal moves, and it’s possible to use positional judgment to sense when more or less potential exists for counterplay. But it’s still hard.

In the above position, after white plays Be3, black doesn’t have any useful moves. I think it’s pretty easy to see that they can’t defend or move the a6 pawn. What’s harder to see is that they don’t have anything else — no threats, no taking the initiative, no pawn breaks.

Having analyzed this position with an engine, I can now report that they don’t. In the game, I was less certain, but I played the correct move and it worked out.

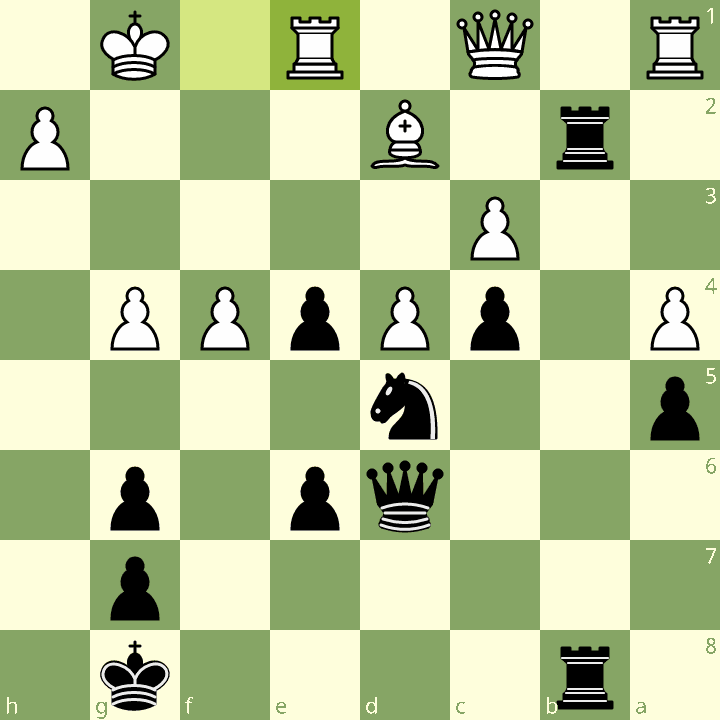

Another example. I got this position in a tournament game a few years ago and played g5. Can you find something better?

The best move, confirmed by postgame engine analysis, is either Qe7 or Qd8, planning Qh4, with decisive infiltration of white’s kingside. I actually had this idea during the game, but couldn’t sufficiently prove to myself that white had no counterplay. Trying to prove that my opponent had absolutely nothing useful, during the vast amount of time I would give them while making two consecutive quiet moves, felt a lot like searching outer space for a teapot.

I posted this on social media at the time, and I got some responses that missed the point. “Well, what can white do?” some people said. That’s the wrong question. We know, thanks to Stockfish, that the answer is nothing. But I don’t have access to Stockfish during the game. The right question is, during the game, how do I reach that conclusion — that white can do nothing — with a satisfactory degree of certainty?

The chess board isn’t outer space, but the number of possible positions after two moves (four ply) number in the hundreds, if not the thousands, depending on the position. You can’t consider each one individually.

So, what can you do?

I do think it is possible to improve at limiting your opponent’s counterplay, but it takes some work. All three of these steps are required.

Recognize that it’s hard. If a book or video explains a move in some GM game as “preventing counterplay”, and then moves on to the next move, know that there’s likely quite a bit of calculating and evaluating that they’re glossing over. When you try to limit your own opponents’ counterplay, you won’t be able to skip that step.

Use calculation and positional understanding. In both positions above, the opponent’s forcing moves go nowhere, and their pieces are uncoordinated and poorly placed. It will take a while before they can meaningfully attack any weaknesses we have. If you can see all that, then you can recognize that they have no counterplay, and that we have the flexibility to play a quiet move.

Trial and error. Play a lot of games, get into a lot of different kinds of positions, calculate, evaluate, and if you don’t see anything your opponent can do, trust yourself and play your move accordingly. If they surprise you with something you didn’t anticipate, that’s a learning opportunity (hopefully you have some way of remembering it), and that’s how you improve.

For me, preventing counterplay is something that’s a lot harder to do in blitz than in classical. I usually can’t do it properly without spending multiple minutes on the move. Your mileage may vary.

I made this meme a while ago because it seemed like when there was a move that didn’t improve a piece or create a threat, and it was good, chess authors called it “preventing counterplay”, and when it was bad, they called it “passive”. How to tell which was which in your own games seemed underexplored.

But the difference does not need to be so mysterious.

Every quiet move is an act of faith. You’re choosing to believe that you’ve seen all the ghosts in the position, and there aren’t any more hiding. If you’re playing enough games to see that faith pay off in some cases, and maybe backfire in others, and if you’re confidently making the moves that your calculation and evaluation say are good, then you’re doing it right, and in the long run you’ll do well.

Nice post Dan. The part of the game where your positional squeeze worked and then you don’t know what to do next is to me one of the hardest areas of chess. I also think it’s a key differentiator between masters (and above) vs. everyone else. Hard thing to train but perhaps solitaire chess using games of positionally strong players is a worthy approach.

"Every quiet move is an act of faith." A beautiful idea, beautifully expressed.